About Task Scheduler 2.0, and Why You Should Never Disable It

In NT6 (Vista), a major kernel and subsystems redesign occurred. The refactored subsystems are still used in Windows 10 for desktop applications, thus are still important, especially after the arguable ‘failure’ of Windows 8 Store Apps.

The subsystem in question here is the Task Scheduler. In Windows XP and before, when an application wanted to start itself at user login, it would usually add itself to either the user or machine ‘Run’ registry key. Then, when a user logged in, Windows would enumerate values in the applicable Run registry keys and launch those programs.

Microsoft knew they needed something more powerful. The Task Scheduler already existed, as v1.0, but it just wasn’t robust enough. So, they rewrote it, and it became the Task Scheduler 2.0, which is awesomely robust, despite it’s annoying COM based interfaces (increasing abstraction was vogue at the time).

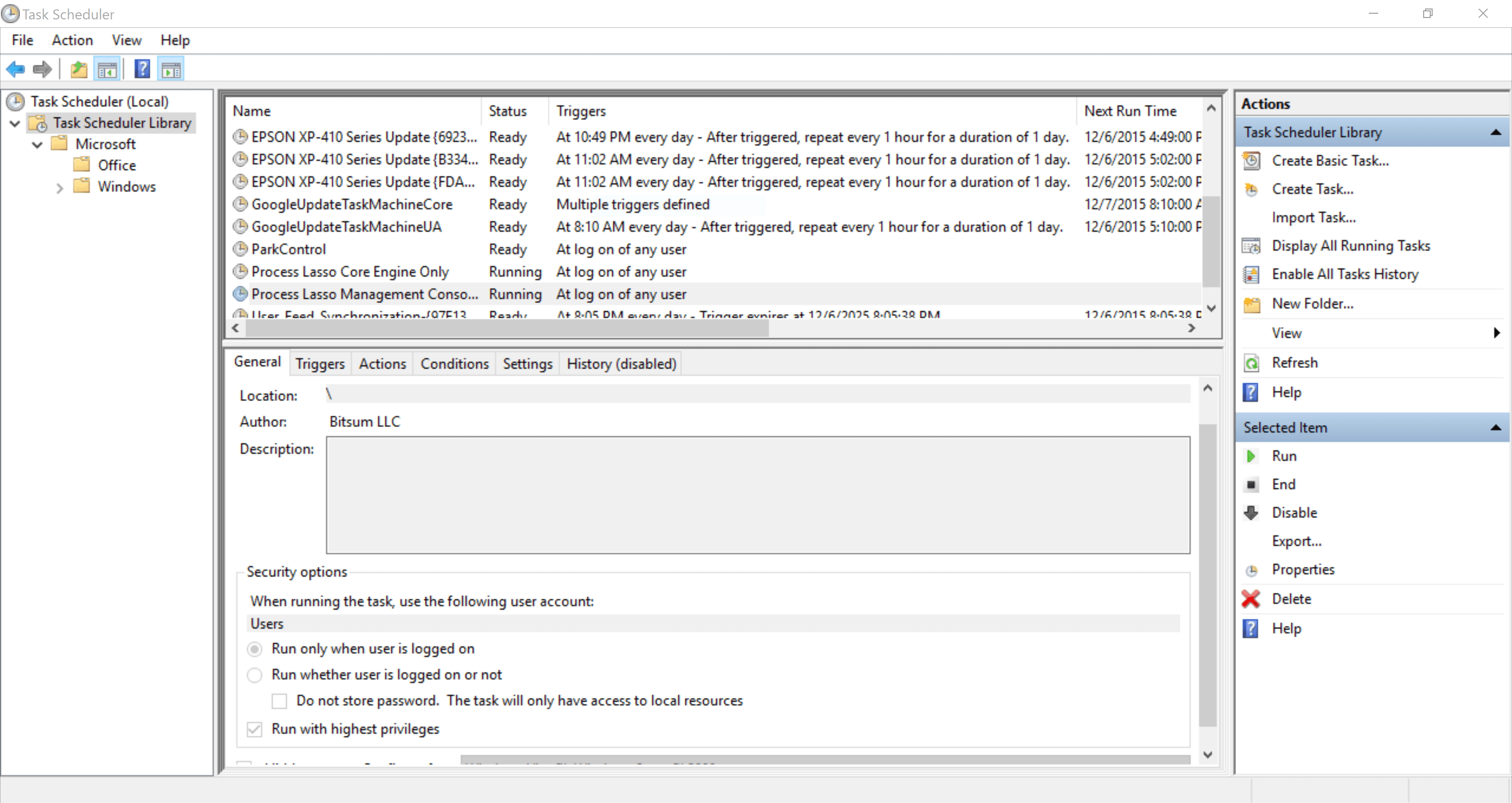

This new Task Scheduler 2.0 could launch programs at user login, at a specific time, or upon many other events, and with many attached conditions (e.g. don’t run if on battery power, or stop after X minutes).

So, now, modern applications written by any developer ‘in the know’, usually use the Task Scheduler to automate not only their application’s launch at user login, but also maintenance tasks, like update checks or garbage cleanup. At Bitsum, we only use it to launch our applications at user login.

One other big advantage of using the Task Scheduler to launch apps is that you can set the application to start with administrative rights without inducing a UAC prompt. This makes sense, as only administrative rights can create a new task to start with. In contrast, when programs that require high rights are started by the classical registry keys, a UAC prompt is induced.

When the Task Scheduler starts programs at user login, it does so *last*, and does so in a throttled manner, knowing that launching all of them at once would be less than optimal. That is why it can take 30 seconds for some applications to show up in the system tray after login. Further, the Task Scheduler has a low I/O priority, and the processes it launch actually inherit that – though they can, of course, adjust it themselves. In other words, it launches processes in a manner that tries to be unobtrusive.

Why am I covering all this? Well, it’s important to know what the Task Scheduler does, because I *often* hear errant advice recommending that people disable this, and other, critical Windows services. These services do NOT consume any real resources just sitting there. Any non-referenced memory will get paged out as necessary by the virtual memory manager, and any CPU use is sure to be negligible, depending on the service maybe, but *definitely* the Task Scheduler’s CPU use is negligible.

Worse, disabling the Task Scheduler means none of those programs start at login, nor maintenance tasks by both third-party applications and Windows components themselves get done. It’s just not worth it. Disabling the Task Scheduler is an irrational suggestion based on misunderstanding and the, reasonable, idea that disabling as much as possible is a good thing. In fact, you need to take a more disciplined, tested, rational approach to choosing what core OS components and applications to disable.

I hope this short post helps clear the air about what the Task Scheduler is, does, and why it should never be disabled.

Discover more from Bitsum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.